Our Psychological Contract

We are hearing in the news from a number of large employers who are announcing their future operating models. Many are referencing that they are implementing a ‘work from anywhere’ or ‘hybrid’ working model. Many more will follow this pattern. So we know that whatever lies ahead will be different to anything we have experienced before. In light of that, I wanted to explore a question that I’ve been wondering about for the last month or so. I am aware that many organisations have been applauded for their significant efforts to create flexible working conditions and for helping their employees navigate the changes to working life.

Yet I see a disconnect between this commendable response to the pandemic and the ‘felt experience’ of being at work for employees, which is often described as overwhelming.

We know employees are grateful for the response of their organisations - but if the employers are already doing what they can, what other choices are there to reduce this significant loss of work-life balance? Can employees do anything to change this? Is it time for employees to renegotiate their workplace ‘psychological contract’ with themselves? I wonder if we now have a unique opportunity to be more deliberate and intentional about the future of work we create for ourselves.

Below I will explore what I think is going on psychologically in relation to the new felt experience of being at work, as it is more than simply gearing up with the latest tech and finding a suitable corner in the home (even though that has been challenging enough in itself). And I look at what both employers and employees can do to help people feel more equipped, more balanced, and more in control.

What is causing the pressure?

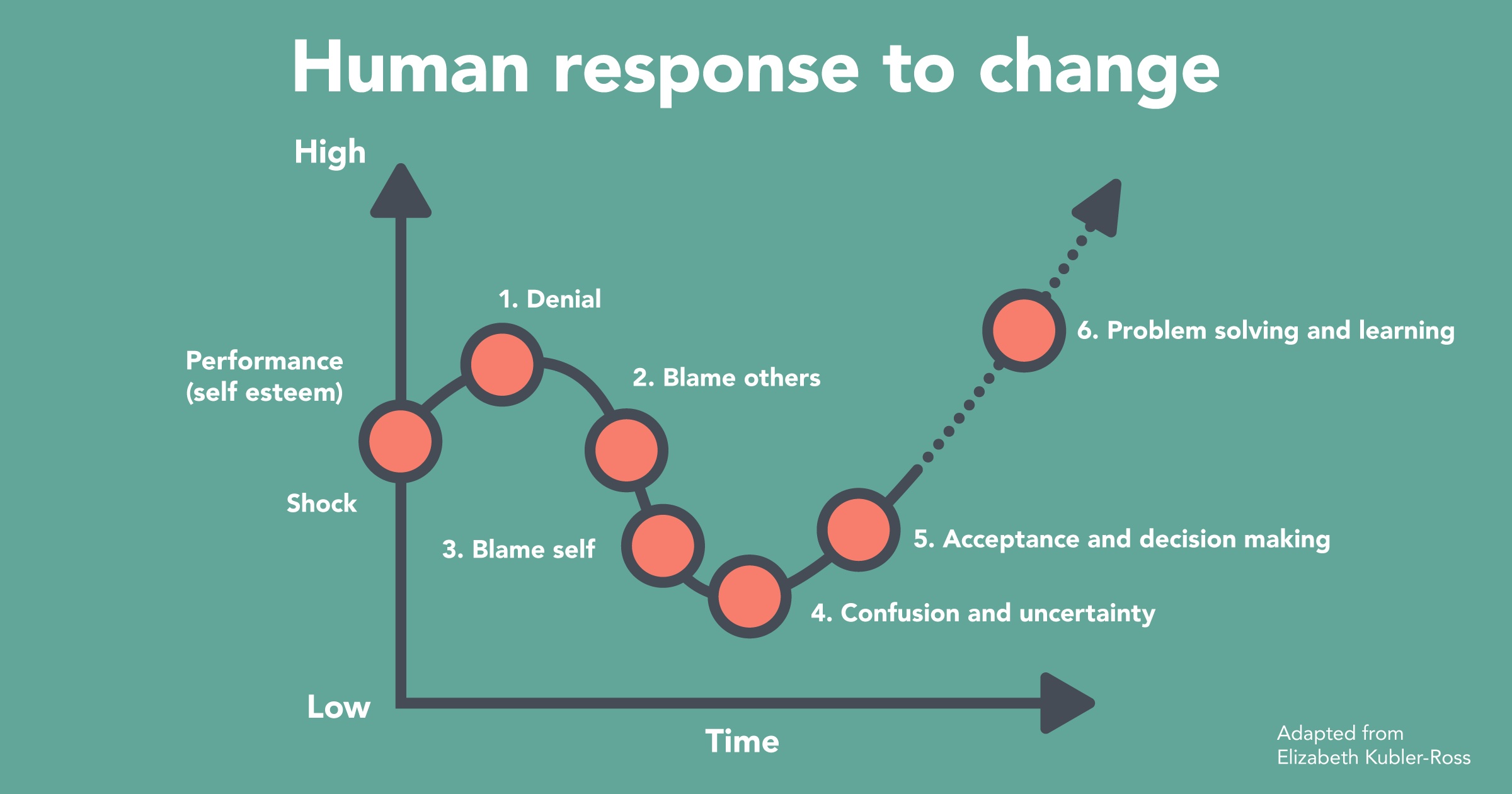

The pandemic has forced a transition away from familiar ways of managing the worlds of home and work, to new ways of trying to balance the complexities of modern life. Many of you will be familiar with the Kubler-Ross ‘human response to change’ curve, below, and you can see that many people are in fact going through a grieving process as they are having to let go of social structures, ways of working and connections that they were attached to. What makes this particularly pertinent is that many people are going through multiple curves for different topics simultaneously: so, adjusting to working from home; having to home-school kids and feeling responsible for their child’s development and social interactions; reduced financial security; worries about family members and ill health; managing insecurity at work as restructures start to happen; loss of social relationships and relied upon connections.

Add to this something that is akin to ‘survivor guilt’ and people take on additional workload. And, of course, many people no longer have the daily commute to work – which was for many the time and space to decompress and ‘let go’. These days, the boundaries between work and home have blurred and it is hard for people to gauge when to stop. By far the biggest issue that I’ve seen raised by the many team members I’ve spoken to is a complete loss of work-life balance.

What is the impact of this?

As people are embarking on this transition, their morale (and self esteem) drops and, as a consequence of this, their performance can also drop. Tasks seem harder, and the busy-ness of trying to fit everything in around additional home duties can have an impact on output. Add to this the very real and significant actual increases in workload caused by the pandemic, and you can see why the impact in psychological terms is so significant.

Reduced morale can also result in an amplified fear or anxiety response. What might be experienced as manageable uncertainty when life is ‘normal’ – can be very destabilising when many other aspects of life are also shaky.

What can help?

Employers

Much has been written on what employers can do to help create more balance. Indeed many of our clients have invested considerable time and effort in creating Flexible Working solutions; setting up ‘No Meeting Fridays’, and deliberate ‘social time’ put into the diaries, together with the myriad of self-help tools that employees can draw on. In my view, I think that employers could focus on a small handful of things but just do them relentlessly and repeatedly:

- Listen and create spaces of Psychological safety (find out how people are feeling and really care)

- Amplify and repeat the things that work really well. Also show appreciation and help people feel seen and valued

- Provide resources to help people help themselves (online tools, mindfulness sessions etc.)

- Communications (both formal and informal) – keep reiterating messages of support and give lots of information, especially about organisation changes

Employees

A key goal during these times is to help employees recognise and develop their own sense of agency. Most people have far more internal resources than they give themselves credit for, and so the work is to help employees notice their own innate capabilities for coping so they can feel more resourceful. This is less about offering expert input or ‘training’ on how to be resilient, but rather creating spaces for team members to discuss and share their own practices for how they can cope.

Also explore how the employees’ own mindset could be holding them back. For example, they may not be giving themselves permission to say ‘no’ or ask for help or renegotiate deadlines. So, leaders might want to take a more psychological and live coaching approach in helping their team members work out for themselves how to cope rather than seeing the challenges as things that must be fixed by the employer.

- Coaching colleagues to be curious about where their ‘dutiful’ mindset comes from and what is preventing them for establishing boundaries, saying ‘No’ and asking for help. Help team members reflect on what matters to them most about their work and where they derive meaning from work

- Taking a strengths-based approach to coaching can also help. Asking the employee to describe examples of when they have coped with ambiguity in the past, what their strengths were then and how those aspects can be re-ignited now. Allowing people to recognise and value their own innate capability for coping

- Coaching people to think about what might help them (like re-claiming a ‘commute’ time and ring-fencing time in the calendar for decompression). Helping them take time for physical breaks…so walks, exercise and fresh air.

- Inviting employees to renegotiate their own deal with themselves as to what is OK at work (so helping them switch off email at night / weekends etc.) to help them let go of unhelpful habits of thinking that somehow ‘glamourises’ the 12 hour working day

Conclusion

Of course, no employer has control over the multiple pressures that employees are facing when it comes to juggling the complexities of post pandemic life. So, it seems that the work of leaders, and indeed teams, right now is less about ‘doing’ things differently and instead helping people ‘be’ different. It’s about helping employees find their own voice and give themselves permission to rest, say ‘no’ or ask for resources. The world of work will not be about ‘going back’ to normal, but instead it will be about ‘going forward’ to a new reality and we need to think intentionally about what we want to create, and how we want to work in that new context.

Further reading

If you are interested in the challenges of leading and developing teams during a pandemic, we;'d recommend Andrea's article on the New Teamwork and Johnny's piece on post-pandemic leadership.

Deborah Gray

Deborah Gray

Aoife Keane

Aoife Keane