What is… the human response to change in business?

The human response to change is the psychological process everyone goes through when faced with significant change and/or a perceived sense of losing something we value.

In organisational life we all have needs that get met from our working environment. These can vary but they are important to us (even unconsciously!) for example; a need for control, a need for security, a need to feel like you’re making a difference or having an impact, or a need for social connection. In organisational change, we might perceive that one or more of these needs may no longer get met, and thus we can be catapulted into the curve as we come to terms with losing those things we value.

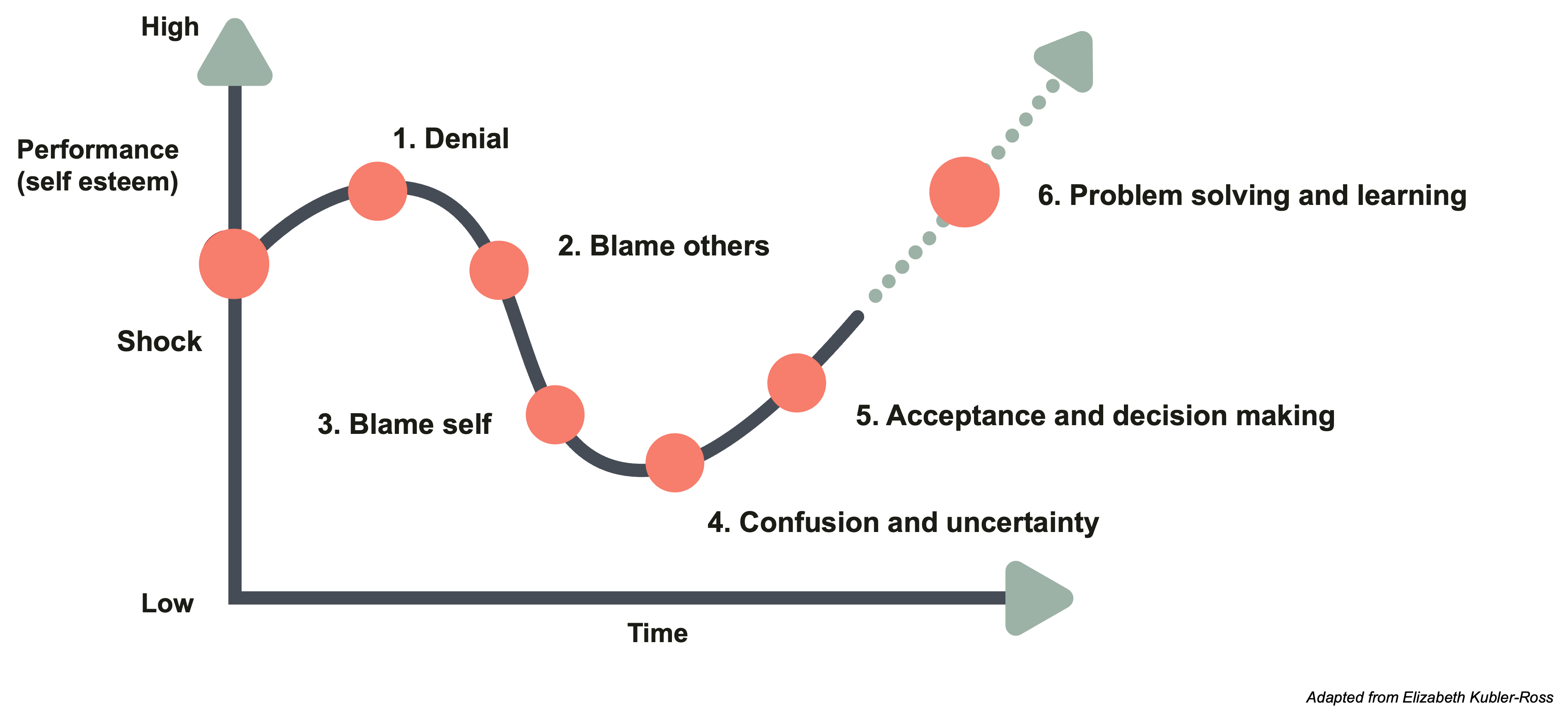

Our understanding of the human response to change lies in Elizabeth Kubler Ross’ psychological study where she articulated the five stages of grief. She soon realised that this process is equally likely to happen in the workplace as people go through any number of different changes, like restructures, redundancies, personnel changes, etc. And if a change requires you to give up something you value it is likely to trigger the process.

Most people are familiar with this curve, but in short it maps one’s journey through the stages of the change process, and the effect on self-esteem and performance over time. While we’re still feeling relatively effective at the early stages of the curve, as we get more into contact with whatever the change entails, we progressively move down into self-blame and confusion, resulting in drops in self-esteem, and ultimately, productivity. It’s striking that organisations engaging in largescale change and transformation programmes do not plan for or attend to this dip as it can have a material impact on both the pace and effectiveness of the project.

SHOCK: When first presented with the change, we might struggle to take everything in.

DENIAL: You’re inclined to push the change away believing things like ‘it’s not going to happen’ or ‘nothing’s really going to change, I can keep doing what I’m doing’.

ANGER/BLAME: The instinct is to blame the change initiators, ‘they don’t know what they’re doing!’ or ‘they haven’t thought this through!’.

SELF-BLAME: This is the personal anxiety, rife with thoughts like ‘I’m not good enough’, ‘I won’t make it because I can’t do my job’.

CONFUSION/UNCERTAINTY: Here we feel resourceless, lacking in energy and ill-equipped to do anything about the situation.

EXPLORATION: Here we’re coming out of the nadir, starting to be more curious about options and being more thoughtful about how we could adapt to the change.

ACCEPTANCE AND DECISION MAKING: This is the final stage where we have come to terms with the change and are ready to make a decision on our own path forward.

What is at stake if organisations don’t attend to the human system during transformation?

No one can completely remove all of the psychological noise from change – we’re humans and it’s inevitable – but leaders can create safe containment for people to help them process the change more quickly. This both eases their change experience and helps avoid disrupting the wider change process.

If leaders don’t take the impact on their people into account, they risk:

- Drop in productivity due to languishing in the ‘low esteem’ part of the curve

- Divisive culture where people are either fired up and angry, or demotivated and disengaged

- Disrupted change process due to poorly addressed resistance

- Damaged reputation

The culmination of these factors can risk the overall success of the change initiative in that it may take longer and cost more to implement than originally planned. So it makes good business sense to pay attention to employees’ felt experience.

What has Sheppard Moscow done to support organisations through their human responses to change?

One global financial institution was restructuring and seeking to integrate two previously separate teams. The business rationale for this integration were clear but nevertheless, a number of people were impacted in different ways ranging from a loss of certainty around job security and change of contract terms, or a change in working location involving, in some cases, unexpected and unplanned for relocations to new countries. This caused great uncertainty not just around personal family and living situations, but future career options with the institution. People immediately dropped from thinking at a strategic level to being concerned with immediate needs – can I put a roof over my head? Can I pay for my children’s education?

As a part of our approach with the financial institution, we paid close attention to these three key elements which are relevant to all change programmes.

Optionality to empower

People need a sense of control and agency to feel anchored and strong at work. In the change process, you need to try to maintain a vestige of that, for example offering a sense of optionality. There will be some non-negotiables, but is there room to help people shape their own path? In our example above, we asked people who were being moved around what they were interested in, then we looked for options to present to them. The majority of people found something they wanted rather than being sent away without any control.

Listen, listen, listen, listen and then listen more.

Through any change process, organisations need to feather through aspects that are about responding to the human experience of that change as well as the structural transformation elements of the process. This means canvassing from early on, talking to people about how they feel about the change, their concerns and what help they might need to get through it. There must be a climate of psychological safety so people can speak freely about their worries and what they don’t like.

Leaders and change agents will be more effective if they can explicitly acknowledge the strength of feeling they’re seeing, playing back that acknowledgement to people and keeping two-way communication open. Whilst it may seem futile – this degree of engagement is so powerful. You’ll often see big transformation programmes have quite a lot of communications woven in, which is very important – but these communications must be the right type. This means not just talking about what’s happening, but responding to what you’ve heard, to the concerns, worries and fears of people. Even more effective is maintaining a 2-way dialogue. One way town halls, for example, miss an opportunity to make real contact with the people in the business.

As you listen, you don’t have to fix things; it’s the acknowledgement of the emotion that will help people feel seen and valued and help them move through to the next process by themselves.

Resist the futile tightrope

You can see the change curve like a rollercoaster, you have people coming down one side and up the other. Often, the people who are the change leaders are already way over on the other side, already in a position of ‘acceptance’. In this position it’s all too easy to be thinking ‘I don’t know what the problem is, this change makes perfect sense’, and they’ll try and pull people across without allowing them the space to go through the blame and confusion.

This is a futile effort. People will fall off and end up in the ‘washing machine’ at the bottom, stuck in a low esteem/performance cycle without the resource or support to move through to the next stage. Leaders must be wary of this and avoid the temptation to just yank people across.

So, what is the human response to change?

The human response to change is the psychological process in which humans move through various emotional states that are triggered by significant changes happening to them. In the contexts of transformation and organisational change, this process people will go through and how it is handled has significant bearing on the success of the programme.

So if organisations want embedded, pacey and lasting change they must give time and support for their people to experience the curve and find their own path way through it. It makes good business sense.

For further reading on change and transformation, check out Deborah's insight on how to lead through restructuring or its companion piece, 'Five steps to deliver sustainable team integration'.

Deborah Gray

Deborah Gray

Aoife Keane

Aoife Keane